You may have heard more about hard seltzer this summer than any summer before — more specifically, White Claw seemed to be all the rage. Though recent popularity pushed the hard seltzer market to a whopping $500 million business by Q3 of 2019, 85% of that market is controlled by just two brands: Mark Anthony Brands’ White Claw and Boston Beer Company’s Truly. Of that 85% — most of which comes in trendy silver cans with minimalist designs — White Claw controlled 54% of the entire hard seltzer market as of August 2019.

By the end of the summer of 2019, hard seltzer (mostly White Claw) controlled more market share than essentially all US craft breweries put together. Analysts predict that the market will quintuple in size, to $2.5 billion, by 2021. All that is impressive, but the real standout stat is that about 75% of the segment’s 200% growth in the past year has come from just one month: July 2019. So the question in this month’s Unrolling is this: how did the White Claw brand erupt out of nowhere to create a movement? (And are there really no laws when drinking Claws?)

Back to the Start

White Claw didn’t invent the hard seltzer. That honor goes to SpikedSeltzer (which recently rebranded as Bon & Viv), now part of Anheuser-Busch. That brand launched in 2012, and gained enough traction to convince Mark Anthony Brands (MAB) that a similar product would be a good move.

SpikedSeltzer was born at an intersection of a couple of trends that birthed a new opportunity. Beer consumption had been flat or falling — as was soda consumption. Spirits weren’t doing too much better. A growing awareness and adherence to the nebulous principle of ‘wellness’ was pushing people to cut calories where they could. For many, especially many millennials, this meant replacing beer and sugary mixed drinks with vodka-sodas — a drink preferred by 27% of alcohol consumers, according to White Claw’s research.

This is the same environment that lead to the meteoric rise of LaCroix, kombucha, the keto diet, and the gluten-free movement. Hard seltzer fit into that same category of aspirational lifestyle brands and movements. It promised fewer calories than traditional drinks, combined with flavors that were already familiar to the cultural leading edge.

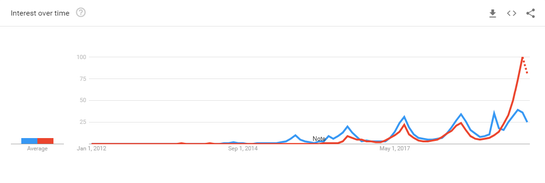

From 2012 to 2016, the hard seltzer market grew slowly, in fits and starts. It would catch the attention of a journalist or influencer, but it hadn't quite caught the popular imagination. The Google Trends graph below (fig.1) is telling — the red line shows searches for the search term “hard seltzer” and the blue is searches for the brand topic “SpikedSeltzer.” The two are mostly flat until 2015, and by 2016 they take off. Unsurprisingly, the light and bubbly adult beverage peaked in the summer months.

Figure 1 — Blue: "SpikedSeltzer" brand topic; red: "hard seltzer" search term

![]()

5 Trends Driving the Hard Seltzer Industry

1. Wellness

Wellness has been adopted as a one-size-fits-all category that covers fitness, appearance, mental health, and a healthy dose of pampering. Unlike traditional fitness or active lifestyle categories, wellness is more than hitting the gym and going hiking or windsurfing on the weekends. It’s been tied to skin care and personal grooming, to natural products and decidedly unnatural supplements like protein and collagen powders. It comes out in hashtags like #selfcare and #livingmybestlife.

Wellness has become a goal in and of itself, as well as an excuse to splurge a little. Products like hard seltzer were in a perfect position to jump on this trend — every product in this category touts low calories (most around 100, the same as a light beer), no added sugars besides those involved in making the alcohol, no gluten, and no sodium. They are a natural fit for a kind of cultural shift from indulgence to indulgence without that bit of guilt thrown in.

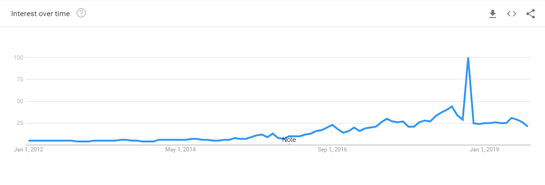

2. The Rise of Regular Seltzer

As an outgrowth of the #wellness movement, the rise of seltzer water and the fall of soda was the precursor to the hard seltzer industry taking off. It’s no coincidence that interest in hard seltzer in fig. 1 matches so closely to interest in LaCroix in fig. 2. LaCroix itself has fallen off the top of the heap, thanks in large part to competition and some comments from National Beverage Corporation’s CEO. The seltzer market as a whole, however, remains strong with fierce competition between legacy brands like Perrier and Seagrams and upstart challengers like Spindrift.

Figure 2 — "LaCroix sparkling water" search topic

![]()

3. Shifting Gender Norms

It may seem odd to talk about shifting gender norms in an article about the brand success of a mildly alcoholic, lightly flavored, summer party drink, but here we are. It’s an important point, because any marketer who avoids addressing the shifting conversation around gender, or falls behind, risks alienating a large part of the market.

In hard seltzer’s case, the conversation isn’t about LGBTQ+ rights, marriage equality, women’s rights, or any of the traditionally polarizing issues that have often been brand minefields. Rather, it’s about the changing face of masculinity and the acceptance by traditional male audiences of things that had previously been considered effeminate or dainty. As this Vox article points out, White Claw succeeds where Zima failed by making it okay to be both macho and to enjoy a lighter drink.

4. Income Inequality

Who knew that the hard seltzer market was such a hot-bed of controversy? White Claw, and other hard seltzers, hit a lot of the notes of an aspirational brand, but at a much more affordable price point than most aspirational products. In fact, a case of White Claw costs just a little more than a case of domestic light beer, but still far less than a case of premium IPA. Lovers of White Claw even specifically call out how inexpensive it is. How can a relatively affordable product, that is universally acknowledged as being relatively affordable, still be an aspirational brand?

The short answer is by being a “lifestyle brand.” The long answer is a bit more complicated. Selling hard seltzer is less of a direct symbol of conspicuous consumption (like, for example, a Mercedes) and more about selling the idea that, while the drink you’re holding may not be prohibitively expensive, it’s only because you’re more interested in experiences — a certain lifestyle that prioritizes shared moments with friends rather than material goods, provided that those shared moments manage to capture whatever the current zeitgeist may be. As millennials find themselves squeezed by shrinking wages and growing housing and education costs, they have increasingly turned to prioritizing experiences (which are often free or cheap) vs. status symbols (which are not). Hard seltzer has embraced this idea, aligning itself with the idea of doing affluent things (boating, festivals, bonfires on the beach, hiking the Appalachian Trail with friends) without needing to be expensive itself.

![white claw illustrations]()

5. Standing Apart

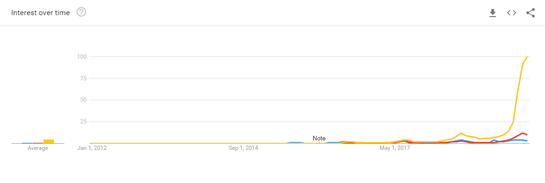

White Claw is hardly the only hard seltzer brand on the market, and the forces that helped shape its success were no different for the competing hard seltzer companies. Yet White Claw stands alone as the definitive winner of the seltzer wars. We intentionally left off searches for “White Claw” on the fig. 1 chart above because it throws the scale completely off — see fig. 3 for an example. White Claw today gets almost 10x the search volume of “SpikedSeltzer” and “hard seltzer” put together. So what did they do right that allowed them to climb to the top so quickly and completely?

Figure 3 — Blue: "SpikedSeltzer" brand topic; red: "hard seltzer" search term; yellow: "White Claw"

![white claw search results]()

Interestingly enough, this was a familiar place for MAB. Before hitting it big with White Claw, they were most famous for owning the Mike’s Hard Lemonade brand, which had a similar origin story. Mike’s Hard Lemonade was a response to Zima and the rise of the wine cooler in the late 90’s and early 2000’s. Like with White Claw, Mike’s wasn’t the first to market, but it had one of the biggest impacts, leading to a flourishing of hard lemonade competitors and the growth of the “alcopop” segment in the early and middle aughts.

But a lot has changed since 1999. When MAB was fighting to make Mike’s a market leader, it involved large television spend and a strong focus on making Mike’s appear manly enough for a manly man to order at a sports bar. While the effectiveness of that campaign is questionable, Mike’s became the unquestionable market leader in little time — beating out both new classes of products like Zima and entrants from established brands Jack Daniel’s Kentucky Lemonade.

The biggest secret behind their success isn’t any kind of proprietary marketing strategy or mix of tactics. MAB clearly knows their way around media and marketing, and has hired some fantastic agencies to help them make their point; but so does Anheuser-Busch, and Brown-Forman, the parent company of Jack Daniels.

The biggest strength MAB seems to have is the ability to read the market well, and the willingness to commit resources to the bets it makes.

Take SpikedSeltzer as a counter example. Despite being first to market, and despite having the collective weight of Anheuser-Busch behind them as of 2016, they still struggle to reach the same iconic status as White Claw. A large part of that may be tied to forcing a rebrand almost immediately after purchase, burning any brand equity that may have been built up. Being first to market doesn’t count for much if no one realizes you were first because your name changed.

The even bigger story of brand success is one of discarding tradition and embracing changing social norms. White Claw, more than any other hard seltzer brand, embraced the ironic, self-deprecating stigma of being a feminine drink, and turned it on its head. Many of the memes made about the drink, including the sponsored parody meme that started it all, feature not dainty and effeminate intellectuals, or a raucous girl’s night out, but bros — evolved bros. The same bros who, a year ago, were drinking Natty Ice by the bucket. Much like the increasingly popular game, Cornhole, White Claw managed to make itself safe for a hyper-masculine environment by both ignoring gender, and occasionally poking fun of it.

Where traditional brands sought to market hard seltzer to a female audience, and thus “gendered” their drinks, White Claw (and to a lesser extent their top competitor, Truly) eschewed gender entirely in a way that hasn’t been seen in beverage marketing before. The message was clear — if you were drinking a White Claw, you were just one of the (gender neutral) guys hanging out with your buds. It’s telling that even the language of idiom isn’t quite up to the task of expressing the right sentiment. White Claw was able to get to the top because it was for everybody, and it was for nobody. It just was an inoffensive, inclusive way to have a good time with friends (the experience).

White Claw also launched with a clear understanding of how product design and social media interact in modern marketing. Pull up a picture of the leading hard seltzer bottles — the one in the previously linked Vox article is a good one. Even in the background, the White Claw can shines and sparkles. It’s a can meant to be Instagrammed, and designed to stand out in photos, even if your phone is (as the kids say) a potato. There are a lot of other things that White Claw’s marketing team does very well, but this is a critical point that I think not enough people are making:

Modern product design has to be about “Will my product show up clearly and be immediately recognizable in the background of an Instagram photo?”

The Roll-Up

There are a couple of lessons to be learned from the success of hard seltzer in general, and White Claw specifically:

- Brands have to be aware of the social context that their products are sold in. It’s no longer enough to rely on old tropes and traditional breakouts of who your product is for. Doing so at best limits your success, and at worst consigns you to being left behind.

- Being first isn’t the most important part of being successful — being committed is. The White Claw brand has a history of putting significant resources behind the bets it takes, and they’ve paid off every time. Brands that have waffled around the edges are more forgettable and often forgotten. Take a strategic approach to assessing your target audience, what your vision is, and commit to an accelerated growth path — all while remembering to be fearless when it comes to pushing boundaries.

- Products have to be designed not just around usability and merchandising, but around visibility and “pop” on social media. It’s not enough for your product to look good on a shelf — it has to look good in a blurry 4 AM Instagram story.

- Contrary to popular belief, there actually ARE laws when drinking Claws.

Last updated on November 17th, 2022.